0:58 AM Introductory Lecture on Statics: the Catenary and the Arch | |

1. Introductory Lecture on Statics: the Catenary and the ArchWhat? Statics?Why begin a course on classical dynamics with a statics example? The reason is that the most important underlying principle of classical dynamics, and much of the rest of physics, is Hamilton’s Principle of Least Action: a system’s time development can always be describes as a path through some multidimensional parameter space (positions, velocities of all its component parts) and the path it actually follows is the one that (on varying the path) minimizes the integral of a certain function, called the action, along that path. A generalization of this principle by Dirac and Feynman (the "sum over paths") led to a fruitful reformulation of quantum mechanics and quantum field theory, now widely used. The mathematical machinery necessary to minimize an integral along a path by varying the path is called the calculus of variations, so that’s what we have to master. To see how it works, we’ll first apply it to a simple example: finding the curve describing a uniform rope hanging between two points under gravity. The “action” for this statics problem is of course just the potential energy. And, to be sure we’ve found the right answer, we’ll first solve the problem by more traditional statics techniques. So this is where we begin. The CatenaryWhat is the shape of a chain of small links hanging under gravity from two fixed points (one not directly below the other)? The word catenary (Latin for chain) was coined as a description for this curve by none other than Thomas Jefferson! Despite the image the word brings to mind of a chain of links, the word catenary is actually defined as the curve the chain approaches in the limit of taking smaller and smaller links, keeping the length of the chain constant. In other words, it describes a hanging rope. A real chain of identical rigid links is then a sort of discretization of the catenary. We're going to analyze this problem as an introduction to the calculus of variations. First, we're going to solve it by a method you already know and love -- just (mentally) adding up the forces on one segment of the rope. The tension is pulling at both ends, the segment's weight acts downwards. Since it's at rest, these three forces must add to zero. We'll show that writing down the balance of forces equation gives sufficient information to find the curve of the chain A Cambridge mathematician, Thomas Whewell, famously stated in unconscious rhyme, And so no force, however great, can pull a string, however fine, into a horizontal line, that shall be absolutely straight. (Trivial fact: Whewell had a way with words -- he even invented some of the words you use every day, for example the words scientist, physicist, ion, cathode, anode, dielectric, and lots more.) A Tight String

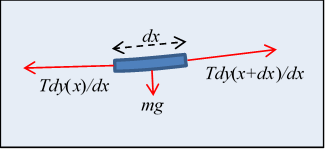

Each little bit of the string is in static equilibrium, so the forces on it balance. First, its weight acting downwards is Representing the string configuration as a curve

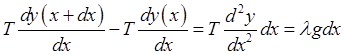

so So the curve is a parabola. Not So TightHowever, there are hidden approximations in the above analysis -- for one thing, we've assumed that the length of string between Obviously, with the string nearly vertical, the tension is balancing the weight of string below it, and must be close to zero at the bottom, increasing approximately linearly with height. Not to mention, it's clear that this is no parabola, the two sides are very close to parallel near the top. The constant

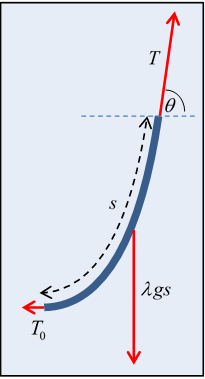

If the tension at the bottom is

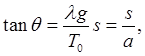

from which the string slope

where we have introduced the constant So we now have an equation for the catenary, Now we've shown the slope is

that is,

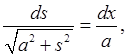

Taking the square root and rearranging

which can be integrated immediately with the substitution

to give just

which integrates trivially to

choosing the origin But of course what we want is the curve shape Recall one of our first equations was for the slope

integrating to

This is the desired equation for the catenary curve We've dropped the possible constant of integration, which is just the vertical positioning of the origin. Question: is this the same as the curve of the chain in a suspension bridge?

Ideal ArchesNow let's consider some upside-down curves, arches. Start with a Roman arch, an upside-down U.

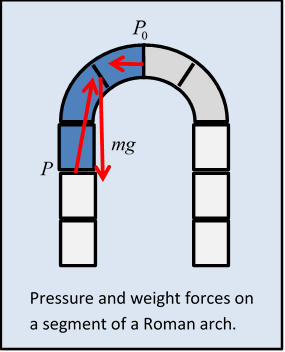

Equating the pressure forces on the arch segment colored dark in the figure, we see pressure on the lowest block in the segment must have a horizontal component, to balance the forced at the top point, so the cement between blocks is under shear stress, or, for no cement, there's a strong sideways static frictional force. (So a series of arches, as shown in the photograph above, support each other with horizontal pressure.)

Let's define an ideal arch as one that doesn't have a tendency to fall apart sideways, outward or inward. This means no shear (sideways) stress between blocks, and that means the pressure force between blocks in contact is a normal force -- it acts along the line of the arch. That should sound familiar! For a hanging string, obviously the tension acts along the line of the string. Adding to our ideal arch definition that the blocks have the same mass per unit length along the entire arch, you can perhaps see that the static force balance for the arch is identical to that for the uniform hanging string, except that everything's reversed -- the tension is now pressure, the whole thing is upside down. Nevertheless, apart from the signs, the equations are mathematically identical, and the ideal arch shape is a catenary. Of course, some actual constructed arches, like the famous one in St. Louis, do not have uniform mass per unit length (It's thicker at the bottom) so the curve deviates somewhat from the ideal arch catenary.

| |

|

| |

| Total comments: 0 | |

Let's take the hint and look first at a piece of uniform string at rest under high tension between two points at the same height, so that it's almost horizontal.

Let's take the hint and look first at a piece of uniform string at rest under high tension between two points at the same height, so that it's almost horizontal.

What he did was to work with the static equilibrium equation for a finite length of string, one end at the bottom.

What he did was to work with the static equilibrium equation for a finite length of string, one end at the bottom.

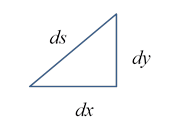

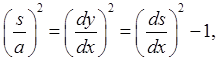

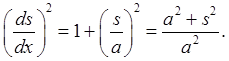

and the infinitesimals are related by

and the infinitesimals are related by

(Notice the vertical ropes are uniformly spaced horizontally.)

(Notice the vertical ropes are uniformly spaced horizontally.) Typically, Roman arches are found in sets like this, but let's consider one free standing arch. Assume it's made of blocks having the same cross-section throughout. What is the force between neighboring blocks? We'll do an upside-down version of the chain force analysis we just did.

Typically, Roman arches are found in sets like this, but let's consider one free standing arch. Assume it's made of blocks having the same cross-section throughout. What is the force between neighboring blocks? We'll do an upside-down version of the chain force analysis we just did. A single Roman arch like this is therefore not an ideal design -- it could fall apart sideways.

A single Roman arch like this is therefore not an ideal design -- it could fall apart sideways. Here's a picture of catenary arches -- these arches are in Barcelona, in a house designed by the architect Gaudi.

Here's a picture of catenary arches -- these arches are in Barcelona, in a house designed by the architect Gaudi. In fact, Gaudi designed a church in Barcelona using a web of strings and weights to find correct shapes for the arches -- of course, the actual building would have a shape like the reflection in a horizontal mirror above the strings -- here's how he did it:

In fact, Gaudi designed a church in Barcelona using a web of strings and weights to find correct shapes for the arches -- of course, the actual building would have a shape like the reflection in a horizontal mirror above the strings -- here's how he did it: